A Rothschild Legacy in Utrecht: Hélène de Rothschild and the Rebuilding of De Haar Castle

‘Never had she seen anything so perfect and harmonieux,’ recalled the acclaimed Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers, known for the Rijksmuseum and the Central Station in Amsterdam, of a 1903 meeting with Baroness Hélène van Zuylen, born de Rothschild, at De Haar Castle near Utrecht.1 On the occasion, the baroness had been admiring the Main Hall of De Haar, the reconstruction of which had been commissioned by her and her husband, Baron Etienne van Zuylen van Nijevelt van de Haar, in 1892. The rebuilding of the baron’s ancestral seat, a ruin at the time he inherited it, would eventually take twenty years, although the castle had been used by the couple for lavish entertaining from 1895 onwards.

A Jewish-Catholic marriage

Hélène de Rothschild and her husband Etienne van Zuylen first met in Paris around 1886, according to family legend, at a bal masqué where he, dressed as the antique hero Hercules, ‘swept her off her feet’. 2 She had been born in 1863, the only child of Baron Salomon James de Rothschild, whose father James Mayer had been the founder of the French branch of the Rothschild banking firm, and Baroness Adèle Hannah Charlotte von Rothschild, who came from the German part of the family. Hélène’s father had died young, and she had been raised by her mother and her uncle, Mayer Alphonse de Rothschild, who acted as legal guardian. By contrast, the Catholic Etienne van Zuylen came from an ancient, noble Dutch-Flemish family, and it is thought he was a cavalry officer at the time of their first encounter. He lived off the shares, bonds, and rents from the estates his family owned, but this was not enough to sustain his sophisticated lifestyle. Whether it was a love match is uncertain, but Hélène de Rothschild, as a wealthy heiress of her father’s fortune, could provide Etienne van Zuylen with a more than sufficient income. Moreover, she might have seen him as her ticket to freedom, as her upbringing had been just as rigid and shielded as it had been privileged.

In any case, both appear to have been quite determined to wed, for they resisted the antisemitic and religious objections of his family as well as the religious and financial grievances of hers. Adèle von Rothschild, Hélène’s mother, was a deeply religious woman who had already reluctantly seen two of her younger sisters marry Christian men. She had also expressed a preference to see her daughter marry inside the family. Nonetheless, she could not prevent Hélène de Rothschild from marrying Etienne van Zuylen, although their 1887 wedding was a modest affair, held in Paris in August, the month when most of Parisian high society was out of town.

De Haar Castle and le goût Rothschild

Adèle von Rothschild never visited her daughter at De Haar, yet several relatives did, as well as scions of other Jewish haute bourgeoisie families, such as members of the Cahen d’Anvers, Königswarter, and Stern families. September was the month of lavish entertaining at the castle, as it was traditionally the time of year when the family was in residence, but guests also visited at other moments, mainly during the spring, summer, and at Christmas – which was celebrated in the Catholic tradition. Apart from friends and family, captains of industry, artists, writers, nobility and gentry, members of several European royal houses visited, including the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina, and Queen Mother Emma.

The Van Zuylen-De Rothschild marriage was modern in many respects. Hélène de Rothschild and her husband shared a taste for masquerade balls, travel, horses and automobiles. Moreover, in their prenuptial agreement, the couple had stated the exclusion of all communal property, as well as Hélène de Rothschild’s complete legal competence, as long as her husband’s living expenses would be fully supported. This she did very generously, through monthly cheques and extra funds whenever he needed them. She also frequently donated money to charitable causes, especially those focusing on the arts, literature, and animal welfare.

Besides their residences in Paris (avenue du Bois de Boulogne 86) and Brussels (avenue Louise 84), around 1900 the baronial couple also had an eclectic, Italianate villa built in Nice, on the boulevard de Cimiez, by the French architect Constantin Scala. De Haar Castle, however, was undoubtedly their greatest achievement. The restoration of the Van Zuylen ancestral seat to its former glory, was much more Etienne van Zuylen’s project than that of his spouse. She rarely joined him on his visits to oversee the rebuilding. What is more, an onlooker observed that she did ‘not even turn her head for a moment’ when driving past De Haar in her car in 1902 – which was probably an exaggeration but suggests a lack of interest. 3 Nevertheless, despite Hélène de Rothschild’s more distant relationship with the castle and the nearby villagers of Haarzuilens, she was more than just the supplier of funds for her husband’s life’s work.

On their travels to the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), Egypt, British India (India), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Japan, and the United States, Hélène de Rothschild and Etienne van Zuylen bought a varied collection of furniture, art and antiques, and even animals for the De Haar estate. Although she bought what she liked, rather than as a connoisseur, the baroness probably had a solid knowledge of arts and antiques, as she had spent her teenage years among the collection of her parents, held at their Parisian neoclassical hôtel Salomon de Rothschild. Moreover, she also made her mark on the interiors of De Haar, in which she was likely also influenced by the grand city palaces and country houses of her extended family, many of which she had probably visited in her youth. These must have included her grandfather James Mayer de Rothschild’s Château de Ferrières near Paris, the Château Lafite Rothschild near Bordeaux, purchased by her uncle and guardian Mayer Alphonse de Rothschild, and possibly also Tring Park in Hertfordshire, the country retreat of her maternal aunt Emma Louisa, Lady Rothschild.

In the private suites of De Haar Castle, the Gothic style preferred by the couple’s architect Pierre Cuypers had to make way for le goût Rothschild, which was represented by an eclectic mix of gilded and plastered ceilings, heavy textiles such as brocade and velvet, and wooden panelling and parquet floors inspired by the Renaissance, the Baroque, and eighteenth-century French styles. At De Haar, this eclecticism resulted in rooms in various European neo-styles, accommodating a variety of modern comforts. Occasionally, the attempts to unify Medieval building principles with the baronial couple’s high demands could end in a struggle over the smallest details. For example, as Cuypers did not want visitors to see the white, French-style door of Hélène de Rothschild’s bedroom from the neo-Gothic Hall, he designed a second, wooden door to portion off her apartment.

Very interesting are the frequent references to the Jewish heritage and family background of the baroness at De Haar. The Rothschild coat of arms appears above the fireplace in the library, and above a doorway in the Knight's Hall, next to the Van Zuylen coat of arms. The heraldic symbol of a hand with five arrows, representing the five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild and Gutle Schnapper, who founded the Rothschild banking house, are clearly visible at floor-level. In the Knight’s Hall, Magen Davids were applied to the Medieval beams, while the six-pointed star was also incorporated in the floor of another room on the ground floor. Around 1900, the family crest uniting the Van Zuylens and the De Rothschilds – writing the latter into the history of an ancient Dutch-Flemish noble family – also featured on many utensils used around the home, such as on bed and bath linen, and on coach doors.

Death and legacy

In 1912, while on his way to De Haar for Christmas, Hélène de Rothschild’s eldest son Hélin van Zuylen lost control of the steering wheel of his car, and died in the ensuing crash. This meant a caesura in Hélène de Rothschild’s relationship with the castle. She had always spent less time at De Haar than her husband, with his sister Stéphanie van Zuylen often replacing her as hostess, but after her son’s death, she rarely visited it again – out of grief and possibly also guilt. After all, Hélin had shared his enthusiasm for race car driving with his parents. She did, however, write the verses for several memorials for Hélin which were established on the estate grounds, and which still exist. In Nice, at their villa Il Paradiso, Etienne van Zuylen and Hélène de Rothschild continued to entertain together throughout the 1920s, yet they led increasingly separate lives. Hélène de Rothschild had become a member of literary feminist circles in Paris already around 1900, organising salons and writing novels, poetry, short stories and plays. She also had several long-lasting affairs with women, such as with the English poet Renée Vivien. In Hélène de Rothschild’s own novel Le chemin du souvenir (1907), the restoration of a family estate, as well as the relationship between the nobility and bourgeoisie, play important narrative roles. Perhaps she was inspired by her own life, although writing seemed more a personal creative outlet than a particularly successful artistic or commercial pursuit.

When Etienne van Zuylen, with whom Hélène de Rothschild had still preserved a good relationship, died in 1934, their youngest son Egmont became Lord of De Haar, continuing the tradition of September entertainments, together with his Egyptian-Syrian wife Marguerite Nametalla. In the meantime, Hélène de Rothschild was living in Paris with the Portuguese writer and feminist Olga de Moraes Sarmento da Silveira, with whom she had begun an intimate friendship around 1918, which would last three decades. At the time of the German invasion of France, her friend arranged their flight via Portugal to New York, where they spent the Second World War in the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue. Egmont and his own family stayed in a hotel around the corner. After the war, Hélène de Rothschild moved to Lisbon. She did not find the strength to travel back to her apartment in Paris, which had been completely wrecked and looted by the Gestapo. Despite numerous attempts by the Nazis to expropriate De Haar Castle, including an effort to confiscate the estate in 1944 on the grounds of Jewish ownership, the tricks and schemes of its Steward, Hendrik de Greef, had prevented its seizure from ever happening.

Hélène de Rothschild died of heart failure in 1947, at the Hotel Avenida Palace in Lisbon. Interestingly, her death certificate mentions De Haar as her place of residence. After her body had been treated according to Jewish ritual custom, she was buried in the Jewish part of Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, before being interred in the crypt of the chapel at De Haar in 1958. One year earlier, her granddaughter Marie-Hélène van Zuylen had married her own third cousin once removed, Guy de Rothschild. Together with her brother, the heir apparent Baron Thierry van Zuylen, and his wife Gabrielle Iglesias y Valayos, the family would continue to invite the European aristocracy as well as famous international actors and socialites to De Haar, thus continuing the tradition of fabulous entertaining at the castle into the third generation.

In the Netherlands, the name of Hélène de Rothschild is unmistakably connected to De Haar. Although it has often been denounced as a ‘neo-Gothic fake castle’ in the past, nowadays it is appreciated as an un-Dutch, iconic construction of its time, and a Gesamtkunstwerk of various styles and influences. The largest castle in the country in terms of floor print, it attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Without the full support, the fortune and the mark of Hélène de Rothschild, its restoration would never have been possible.

Dutch Jewish country houses in the modern period

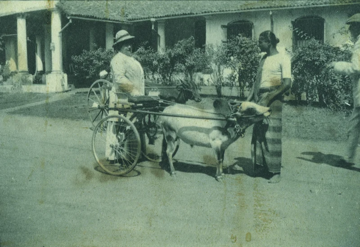

Hélène de Rothschild photographed buying a small ox and hackery cart for the castle, in Ceylon, 1910. The baroness and her husband intended to establish a small zoo at De Haar. Image: De Haar Castle website.

In many ways, De Haar is a unique Dutch Jewish country house. First and foremost because it seems to be the only modern Jewish country house in the Netherlands that is at present publicly accessible as a museum. Its size also distinguishes it from most other Jewish country houses in the Netherlands, which were often newly-established, purpose-built villas, and, to a lesser degree, older country houses purchased, rather than commissioned, by their Jewish owners. Moreover, De Haar was not Hélène de Rothschild’s permanent residence – far from it even –, whereas most of the other houses belonging to Jewish families were. Additionally, De Haar was situated in quite a remote area, as opposed to the mostly semi-rural commuter villages where Dutch Jews established their country houses in the modern period. Its interior, too, was unique. Although its neo-Gothic style reflected contemporary Dutch trends, the visible presence of le goût Rothschild set it apart.

In terms of how De Haar was used, it also differed from most Dutch Jewish country houses, where the nuclear family, as well as business and philanthropy, played an important role. De Haar was meant for entertainment, and Hélène de Rothschild, her husband and her children were never necessarily in residence at the castle all at the same time. Although she did choose to donate much of her inheritance to charities, there is no evidence of her organising any charity events at the castle, while she did occasionally organise these in Nice. And where many of the modern Jewish country house owners integrated in their new environments, participating in local committees and local politics, and sometimes functioning as ‘lords and ladies of the manor’, Hélène de Rothschild was rarely seen at the castle or in the village of Haarzuilens.

De Haar Castle seen from the west, with the Châtelet on the left and the freestanding chapel on the right. Image: author, 2020.

Whereas other Dutch Jews did have international guests and family from abroad staying at their country houses, while at the same time identifying very much as Dutch citizens, Hélène de Rothschild, despite being a true cosmopolitan, very much remained French in her manners, and more specifically: Parisian. Indeed, it was mainly in terms of her hobbies that Hélène de Rothschild resembled other Dutch (Jewish) country house owners: collecting, cars, travel, and literature all played a part in the lives of others, too.

Perhaps one of the reasons why Hélène de Rothschild’s role at De Haar is not better known throughout the Netherlands is that her family’s banking house never had a Dutch branch. But because of Hélène de Rothschild, the Netherlands does possess an important memorial of the Rothschild legacy in stone, and a reminder of a family that has been tremendously important to the modern economic and cultural history of Europe. Yet as Baron Guy de Rothschild, husband of Hélène de Rothschild’s granddaughter Marie-Hélène van Zuylen, pointedly argued in an interview with a Dutch newspaper at the publication of his autobiography in 1984: ‘To be Jewish and rich at the same time arouses suspicion. That is why we, Rothschilds, sometimes lose on both counts.'4 While historic antisemitism has always hindered the proper consideration and analysis of this family’s heritage, in the Netherlands, as elsewhere, it appears the fact that De Haar is open to the public as a museum at least restores some of Hélène de Rothschild’s legacy as a champion of Dutch Jewish heritage.

Sietske van der Veen is a PhD candidate affiliated with the Jewish Country Houses project. At the Huygens Institute (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences) and Utrecht University, she researches the Jewish Dutch elite between 1870 and 1940.

An earlier version of this article was presented as a paper at the British and Irish Association for Jewish Studies Annual Conference in London in July 2022.

For a list of consulted source material, please refer to the short biography of Hélène de Rothschild written by the author in the Online Dictionary of Dutch Women.

The author wishes to thank Abigail Green, Isobel Muir and Briony Truscott for their valuable feedback, and Katrien Timmers for providing a copy of the very useful book Tien eeuwen Kasteel de Haar.

1 Jacqueline Heijenbrok, Guido Steenmeijer and Katrien Timmers eds., Tien eeuwen Kasteel de Haar. Wat een weelde (Amsterdam 2013) 212.

2 Ibidem, 225.

3 ‘Die Haghe’, De Nieuwe Courant, 28 September 1902.

4 Angeline Arnken, ‘Guy de Rothschild: Ik blijf een gewone jood’, Algemeen Dagblad, 21 July 1984.