Sir David Lionel Salomons (1851-1925) is best known for his groundbreaking work on electricity, as a pioneer of automobiles in Britain and for his outstanding watch collection. However, he was also an innovative photographer. He acquired a camera when he was a teenager and built himself a perfectly equipped studio and darkroom, then a projection theatre, where he projected optical lantern slide shows and eventually also kinematograph films.

David’s mother, Emma Abigail Montefiore, died when he was only eight. His father, Phillip Salomons, a London-born Jew, financier, and Sheriff of Sussex, passed away just eight years later, in 1867. Sixteen-year-old David and his younger sisters moved to Broomhill, the country estate (near Tunbridge Wells) of their uncle Sir David Salomons (leader of the struggle for Jewish emancipation, M.P, and previous Lord Mayor of London), and became his wards. In 1873, Sir David died and David Lionel inherited his uncle’s estate and baronetcy. Young David owned a camera in his early days at Broomhill. In the late 1860s and early1870s, he learned to develop his own photographs and carried out photographic experiments. He photographed his uncle and sisters, the Broomhill staff, and some of the guests who came to stay.

David Lionel’s taste for scientific inquiry was visible early on. The Photographic Journal (15 September, 1868) reported a talk by the esteemed Parisian portrait photographer, Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon in London. Seventeen-year-old David attended and was noticed washing the Frenchman’s print with a sponge to see if it had been touched up.

His informal early photographs reveal his creativity and sense of humour. For example, uninhibited by the ubiquitous classic columns and heavy drapery backdrops of studio photography, Salomons drew Gothic arches on a wooden fence, in the illustrative style of an illuminated medieval Bible, to provide scenery for his photograph of Francis Arthur Lucas [Fig.1]. And in lieu of the usual upright or seated pose of the fashionably dressed, he positioned his friend in an old hooded coat, kneeling on dry grass near the fence.

He also played with formats. His stamp-sized portraits mimicked the earliest British postage stamp (1840), the Penny Black. In one collage, the size of a carte de visite, he changed the text on the top and bottom edge of the stamp [Fig. 2]. In another, he superimposed portraits of his friend Jessie Lucas, on the commercial carte de visite of London photographer Adolphe Beau. A hand at centre-right hides a note behind the stamp to completely obliterate the original portrait on Beau’s card [Fig. 3].

Salomons photographed his sister Laura with her friends Violet Montefiore and Polly Lucas, sister of Frank and Jessie. The girls wore long dark capes and homemade cornettes, reminiscent of the costume of the Daughters of Charity, the nuns of the order of Saint Vincent de Paul. Violet fingers the same rosary beads as the monk [Fig. 4]. He also photographed his friends, Royal Academy Professor Solomon Hart and stockbroker Edward Wagg in unusual poses. He carefully scratched out Wagg’s fashionable sideburns in the photograph to suit the man’s feminine costume — a coquette bonnet, striped shawl and flounced skirt [Fig. 5].

Many photographs in David Lionel’s albums reveal that he also enjoyed dressing up and posing for the camera. On July 9, 1875, The Photographic News reported that he had devised an electrical attachment for a camera, to enable the photographer to set up his apparatus and then retire until a suitable scene presents, which he could capture immediately. He may have used such an attachment for his self-portrait in Tyrolean dress [Fig.6].

What is the story behind David’s photograph of a ghost [Fig. 7]? The Vanitas skull and hourglass symbolize the fragility of life and the inevitability of death, with which he was all too familiar. A close-up view reveals that he added a few teeth to the empty jaws. Was this a prop for a fancy-dress party, a magic lantern show, or a composition for an experiment in spirit photography? Or just another expression of his sense of humour?

In 1873, David submitted thirty photographs that he had taken of his uncle's art collection and developed with nitro-ammonia to the Annual International Exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall. He intended that the photographs imitate engravings [Fig. 8].

Salomons was elected to the Photographic Society in 1887, by then an established photographer, whose name and address were printed on the reverse of his photographic cards. His small image of his eldest daughter, Maud, “a gem of portraiture” in the Society’s annual exhibition, caught the attention of the reviewer in The Photographic News (November 11, 1887) [Fig.9 r and v.].

The following year, Sir David Lionel Salomons patented his Photographic Slide Rule, which helped professional photographers solve problems associated with the focus of a lens and size of aperture. He was now deeply involved in photographic theory, published his findings, and patented his improvements to optical lantern slides and their slide carriers [Fig. 10]. In later years, Salomons used photography as an educational tool and an aid to science.

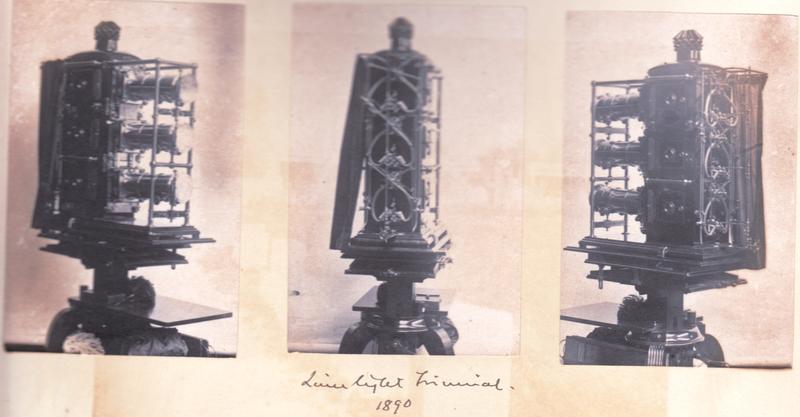

The triple optical lantern, Triunial, enabled one image to dissolve gradually into the next, giving the impression of movement. David Lionel Salomons, 1890.

Note: All the photographs taken by David Lionel Salomons, above, are preserved in the Salomons Museum’s albums 500, 501, 504, 510, 513, and 437. The Markerstudy Group manages the Salomons estate and Museum, http://www.thecivicsociety.org/Salomons.htm. Dr. Chris Jones, the Museum’s curator, kindly assisted with this story.

Dr. Michele Klein is an independent scholar, currently researching nineteenth century Jewish family photograph albums.

https://www.salomons-estate.com