Slavery, Jewish emancipation, and the English Country House

The intertwined histories of slavery and the English country house loom large in today’s debates about the politics of national memory in Britain. These debates caught fire in the summer of 2020, when protests swept the country after the killing of George Floyd. In June, protestors toppled the statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston: a man celebrated for his generosity to the local community, although his money came partly from the slave trade and he himself had served briefly as governor of the Royal African Company, when he was responsible for the transportation of an estimated 84,000 enslaved Africans. Barely ten days later, came the publication of an “Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery”. (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/addressing-the-histories-of-slavery-and-colonialism-at-the-national-trust). This report, which was certainly not a knee-jerk response to Black Lives Matter, unleashed a torrent of public criticism, placing the Trust and its country houses centre-stage in our British culture wars.

Interestingly, no “Jewish” houses feature in the list of 93 National Trust places identified as having strong links to Britain’s colonial past. How then does this contested history relate to the stories we tell through the Jewish Country Houses project? Less, perhaps, than one might think. Writing for Jew Think in late July, Nathan Abrams argued that while British Jews had not been over-represented in the slave trade, they too had a difficult history to confront https://www.jewthink.org/2020/07/31/anglo-jewish-institutions-profited-from-slavery/. What emerges, however, is a complex story that reminds us of the ways in which entrenched patterns of privilege and exclusion shaped Jewish involvement in British life.

Slavery played a central role in the 18th century British economy, while Jews and Jewish businesses played a critical part in London’s evolution as a global financial and commercial centre in the early 19th century. Families like the Rothschilds and the Montefiores were central players in this world and would go onto acquire country houses. Ultimately, however, the prosperity of these families was not tethered to the Atlantic economy in the way that the fortunes of 18th century Sephardic Jewish merchants had been. This was new money, and members of the new Jewish financial elite known as “the Cousinhood” barely figure in the database of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership at UCL, which reflects a more 18th century pattern of wealth and economic activity. More research needs to be done in this area, but it certainly looks as if City Jews benefitted less than we might expect from the financial restitution that came with the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Importantly, moreover, the right of Jews to own freehold property was not secure before 1831 at the earliest. This meant that Sephardic families whose fortunes were strongly linked to slavery could not simply follow the example of British merchants like the Lascelles and the Hibberts by buying into the power and privilege that came with membership of the landed gentry. For families like the Barrows, the Lopes and the Lousadas who did make their money in the West Indies, country house ownership tended to be a stepping stone to conversion and assimilation. That changed in the 1830s, when the campaign for Jewish civil and political rights got underway, but by then Britain had already emancipated its slaves.

Maristow House

The history of two houses in the South-West of England illustrates this transition: both speak to the role of Sephardic Jews in the slave economy of the 18th century Atlantic, and both diverge – not just geographically but also socially and economically – from the world we normally associate with the “Jewish country house”.

Manasseh Masseh Lopes

Maristow House in Devon is an elegant 18th century property, charmingly situated at the mouth of the river Tavy. It was purchased in 1798 by Manasseh Masseh Lopes (1755-1831), a Sephardic Jew from Jamaica, who plainly intended that Maristow would serve as his gateway into both landed society and public office. Manasseh converted to Christianity four years later, when he bought his seat in parliament in the “rotten borough” of New Romney. That year, he adopted his nephew Ralph Franco as his son and heir. Ralph (1788-1854) too converted to Christianity, and in due course he too became both a baronet and a Tory MP. When the House of Commons was asked to vote on the great question of Jewish emancipation, Sir Ralph de Lopes voted against.

the Lopes arms above the window

Maristow has recently been divided into flats, but the small private chapel still belongs to the Lopes family and the Lopes arms feature prominently on the exterior wall. To those familiar with the family’s past, its motto makes uncomfortable reading: Quod Tibi, Id Alii [Treat others as you would yourself]. Manasseh perhaps intended these words as a subtle nod to his Jewish heritage, since they echo both Jesus’ command to “Do unto others as you would be done by”, and the Talmudic variant: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbour; that is the entire Torah”. To a 21st century ear, however, they underline the moral blindness of a society in which high-minded religious platitudes and the horrors of slavery could co-exist side by side.

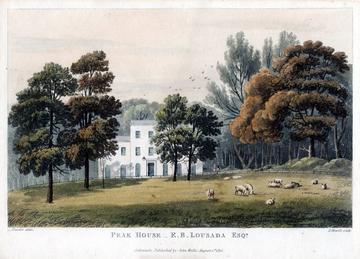

Not far from Maristow, at Sidmouth, stands another Jewish country house divided into flats. Peak House is a much later construction, built in the Edwardian era after a great fire destroyed the original, much expanded Regency house. Like Maristow, that house once belonged to a rich Jew from Jamaica who aspired to join the landed classes. Emanuel Baruh Lousada (d.1832) too had made his money in the West Indies; his nephew and heir, Emanuel Lousada (1783-1854) had recently inherited several hundred slaves at the time of the Slavery Abolition Act. Like all slave-owners, he was generously compensated; the enslaved people themselves received nothing. Once again, the coat of arms of this West Indian Jewish family makes for uncomfortable viewing, with two sugar canes that signal the pride they clearly took in their plantation origins. Here, however, the stories of these houses and their owners diverge.

The Lousada coat of arms (Lancashire Record Office/Molyneux-Seel Papers/John Bury)

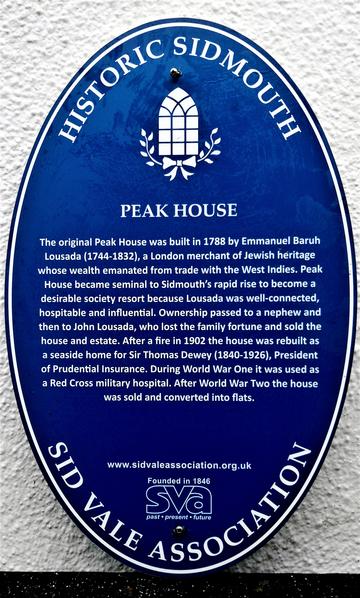

Blue Plaque at Peak House (photo courtesy of the Sid Vale Association)

Unlike his contemporary Manasseh de Lopes, Emanuel Lousada built his house from scratch in what was then a beautiful and isolated spot. Unlike Manasseh, he also intended to remain Jewish. There was a synagogue nearby in Exeter, but in Devon – and rural England - this rendered him an anomaly. Nor did his Jewishness go unremarked. An information board that stood until recently in Sidmouth’s Connaught Gardens recalls inaccurately the time when “The area was all in the ownership of Mr Lousada, who was a wealthy, retired Jew, and the first of his race to risk owning land in England.’

Sidmouth is now a flourishing seaside resort, and local memory attributes that evolution to Lousada. This provided a different kind of platform for entering public life. As a Jew, the second Emanuel Lousada could not become an MP, but in 1842 he was the first Jew in England to become a provincial High Sheriff: something that highlights the connection between land, power and citizenship in this era - and the importance of Jewish country house ownership in the campaign for Jewish civil and political rights in Britain.

That connection between land and emancipation lies at the heart of the Jewish country houses project, although other houses and individuals speak more powerfully to that history. For although Emanuel Lousada remained Jewish his heirs did not: when John Baruch Lousada married his relative Tryphena Barrow in 1832, this marriage took place not in Bevis Marks synagogue but rather in a church at Bath. In this sense, Peak House can be seen more as an ending than a beginning – one that looks back to the history of the Sephardic Atlantic, rather than forward to a future in which dynasties like the Rothschilds were able to integrate into the landed world of the British aristocracy without either assimilating or marrying out.

So divorced was their fortune from the slave economy, that Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore (1784-1885) forged business partnerships with Quaker and Evangelical antislavery activists, like Sam Gurney (1786-1856) and Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton (1786-1845), with whom they founded Alliance Assurance. Together, Rothschild and Montefiore even underwrote the infamous 1833 loan that financed the compensation of slave-owners at what was, apparently, a disadvantageous rate. There was risk in this as the interest was unusually low and the sum involved enormous, but very likely they did it for the glory of being associated with the antislavery cause, in which Montefiore was certainly keenly interested. Yet the complexities of that decision have been lost in the controversies around slavery and abolition that currently dominate the politics of national memory in Britain. Nowadays, we remember not the risk but the reward.

Peak House, 1816

In this context, the history of Peak House matters as the only place where the country house histories of slave ownership that have become such a bone of contention in Britain, and the Jewish histories of emancipation and belonging we seek to uncover, can truly be said to meet. More generally, the absence of Jews from both the UCL database and the National Trust report into properties with histories of colonialism points to the continued exclusion of Jews from key areas of social and economic life in what remains, in retrospect, a critical period in Britain’s national memory. Once rich Victorian Jews were able to buy country houses, they rarely bought the kind of 18th century Georgian properties – built with slave money - that the National Trust has tended to acquire.

Abigail Green

This article was originally published in Aufbau magazine, February-March 2022